What women remember, forget, carry. Intergenerational stories, trauma, survival.

Memory & Trace

By Maša H.

I’ve been continuously creating a dialogue between my mother and myself. In this way, I keep her alive—I keep her close.

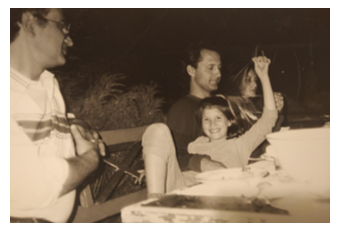

This is one of my most cherished and loving photographs of my mother holding me. I know the story well—how deeply she longed to have a child, how long and painful my birth was. This photo is more than an image; it is a tribute to her tenderness, her open heart, and her unwavering love.

Through her, I learned softness. I learned how to love with depth. And in this work, I honor the gifts she gave me—many of which still shape who I am.

I love you, mama.

The Dialogue

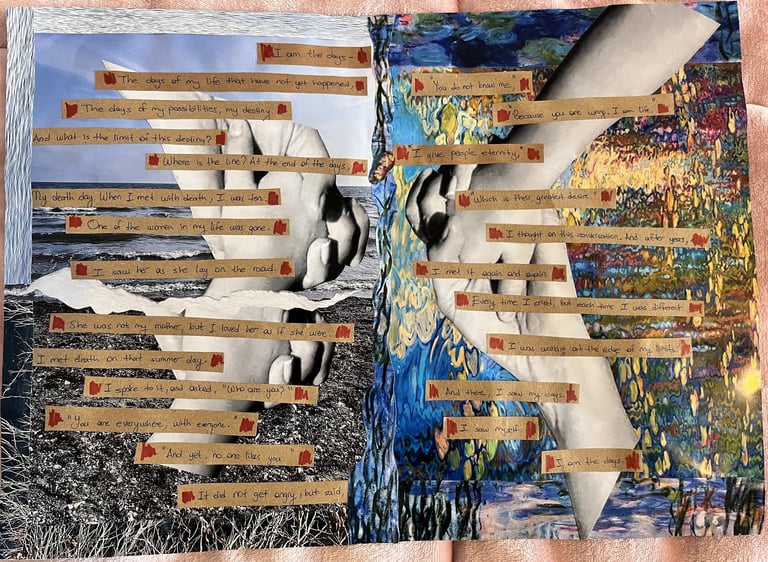

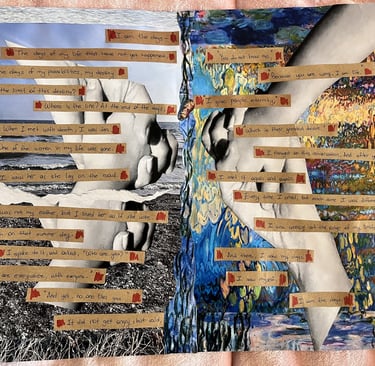

End of the Days

Death

By Beba, 51

Until my father’s death, I had never truly formed any sense of what death meant. Even when my grandmother passed away, I did not dwell on it. But when my father died, after the first wave of overwhelming grief, something within me, quite naturally and entirely unexpectedly, began to feel that death was not an end, but merely a passage into another phase.

I have no philosophical, spiritual, or religious explanation for this, nor do I spend much time thinking about death at all. I simply carry a quiet certainty that when my time comes, I will go to a good place. Death, to me, is where my father is.

And yet, while I rarely think of death, I am acutely aware of life’s transience. It is precisely this awareness that drives me not to let life pass me by. That is why I take joy in the small and simple things, in great and colorful dreams, in journeys, books, and friendships, and above all, in the time I have with the world around me, and with myself.

By Eslem, 25

I am the days

The days of my life that have not yet happened

The days of my possiblities, my destiny.

And what is the limit of this destiny?

Where is the line? At the end of the days.

My death day. When I met death I was ten.

One of the woman in my life was gone.

I saw her as she lay on the road.

She was not my mother, but I loved her as if she was...

By Veronika, 47

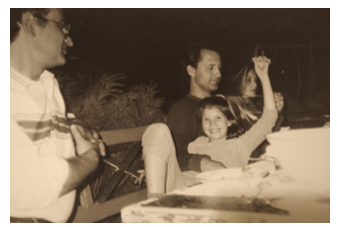

I usually frown in my childhood photos. In this picture, I am showing my oversized teeth in a huge grin. My uncle and I are pulling my hair up in the air. He looks so young, with a wedding band freshly on his ring finger, waiting to be pulled down a year later. His wife – ever so beautiful – poised, majestic, seated next to him wishing she wasn´t there – on a bench at a porch of our cottage in Polabí. She always had bigger dreams, higher hopes. Now she is stuck at my grandparent’s who never really liked her, my cousin peacefully asleep inside her bump. She is gently reaching for an elegant champagne glass, deep in thought. Voloďa, one of my father´s best friends, a Russian Jew, a nuclear physicist, is smiling at me, content. He always brought a lot of Vodka and spring onion with him. I never understood how adults could like that. Little did I know then that he had to leave his wife and kids back in Moscow, to marry a Czech lady to be able to emigrate from the oppressive Soviet regime, to have another son with the new lady, to later remarry his Russian wife to be able to bring her and the family to Czechoslovakia. I learned all that much later. I was just happy to have my belly full, sitting next to my uncle, and be where I was because it was – for a few more years to come - a safe haven.

Untitled

By Maša H.

I have experienced longing in many forms—but the most painful has been longing for loved ones. Whether during the isolation of the pandemic, the dislocation of migration, the quiet loneliness of pregnancy, or the many moves across cities and countries, the ache remained.

I longed for simple things—phone calls, voices, presence. I felt jealousy toward those who had their loved ones just a street away, or a city apart—not separated by borders, and oceans. I missed my sister with a depth that words often failed to hold.

My experience moved through waves—rage, anger, sadness—circling back again and again as I tried to understand the silences and distances that had grown between us. I questioned why my primary family dissolved so completely.

But over time, I have come to accept even the hardest absences. In that acceptance, I’ve begun to learn the quiet, powerful lessons of release. Though I still carry a soft, sacred longing inside me, I hold it gently now—with respect. It continues to teach me about love, impermanence, and resilience.

By Maša H.

While I was expecting my son, I was consumed by fear and uncertainty. His father had just moved to another country without a visa or secure job, and I didn’t know what our future would look like. I carried the weight of enormous responsibility—trying to hold everything together for my family while navigating my own inner struggles, my changing body, and the loss of freedom that came with it.

Pregnancy is often portrayed as the most beautiful phase in a woman’s life. And yes, there are moments of beauty—but it can also be deeply complex, painful, and isolating. This piece is for those who have walked through that shadowed path of pregnancy—whether as migrants, single mothers, in relationships, or simply those whose experiences didn’t match the idealized version we so often see in the media.

Our stories take many shapes. And they all deserve to be told.

The Year of White Walls

by Michelle Mapplethorpe

september;

hospital ward. nurses.

one strips me naked, the other gestures to a scale.

they measure my insecurities —

not underweight enough,

too tall to be understood.

mother blames me.

ten books in a tote bag — no more.

no one tells me how long I’ll stay.

no words upon arrival.

white walls — how well they speak to me.

rooms locked. cameras angled at toilet seats.

I run — fast, screaming.

the colors of autumn evade me.

I kick at dry leaves.

I fail. the lord must know.

how foolish, in this moment,

to meet a mother’s eyes

when both her children are insane.

I blame myself.

december;

chemistry classroom.

sweat beads on an eighteen-year-old forehead.

the dead of winter.

eyes refuse to open, though they try.

a communist desk gripped

by the palms of a child in an adult body.

head spins — wheel of fortune.

faint. faintly remember.

the floor, my only companion — cold, still.

I crawl toward a cushioned seat.

climb. collapse. silence.

march;

police station. a crime.

report it. report it well.

metal bars echo my sighs.

small room. one plant. no light.

a psychologist. a police officer

swinging on the threads of my mind.

came to be a victim,

left a liar.

report says:

false accusation — the red-haired girl is a rat.

june;

lunch break. bathroom stall. a sandwich.

colder days have passed.

flush. the smell of survival —

urine and soap.

words of mockery.

how pitiful the red-haired one has become.

I take a bite.

august;

living room. sunlight tracing scars.

skin pale. dare not step out.

TV laughter — hollow, mechanical.

white walls again. silence.

the phone rings.

“have you eaten?”

have I eaten?

when was the last time I have eaten?

I go to sleep.

Longing

Snow Globe

Family

By Maša H.

In recent years, the theme of family has become central to my work, growing stronger with each move across countries and through different chapters of my life. The distance—both physical and emotional—has made me reflect more deeply on what family means, especially after the loss of my mother. Grief has taken many forms: from numbness to sadness, from anger to rage. I have come to realize that I lost my family as it once was. This collage features one of the few rare photos of us together, taken shortly after the war. I layered it with personal fabrics, papers, and textures to express not only the visible but also the invisible threads that bind memory, loss, and identity. Through this piece, I try to make sense of the disconnection, and to honor what remains.

Blooming Meadow Flowers Turning into a Firestorm

By Š.S.

How midnight thoughts can change your perspective?

As I´m wandering through the silent forest, brand new Airpods are set on the maximum volume my old iPhone allowed me to, sensing my brain will explode any minute (one new notice – you should turn down the volume). Finally, I climbed the last hill in my village (my feet are on fire), before I saw my favorite place in the middle of nowhere (where the foxes say good night).

The forgotten flash of memories is running through my mind, while I barely sit down on a poorly painted bench (it fell apart four years ago). Million scenarios, thinking about her, my dearest best friend (my dearest ex-best friend).

As I can´t stop watching the flashing lights behind the horizon, a lovely thought pops into my mind. Our wonderful “Friday´s champagne session” we had last week (three years ago). While I´m still astounded by such an impressive scene, I´m taking another sip of our favorite liquor, slowly but surely almost empty. Suddenly, I realize that I truly love her with all my heart (I hate you, with all my heart).

The days go by, she is bombarding me with messages, rapidly writing details about every dumb thing happening in her life (narcissist). Remarkable moments, sunsets and sunrises we´ve seen countless times together, photo-shooting at 1PM with a glass of champagne in a treasured place of ours, experiencing the chills all over our bodies, while drinking the sparkling liquid, flowing down our throats (we were most likely alcoholics). Unseparable bond, what a duo we make together, this kind of friendship cannot be found on every corner of the city (luckily).

I'm grateful that I have her by my side (she left me), everybody needs his partner in crime,

or don´t you? Looking forward to our next “session” in the blooming garden of mine,

open fire warming freezing cold bodies, which have no intention to leave the deepest conversations. Swearing, living the best life and sharing secrets (broken promises).

I'll call her in a few hours with an invitation for a karaoke night in a car (you´ve never

picked up), sending a message if she has some plans for tonight (-message delivered, read, ghosted-). Don´t worry darling, we can reschedule it for next week. Thank you for still being my dearest best friend (lies, lies, lies).

Gratefulness, desire, love (fuck this, fuck that and fuck you).

Written by S.S.

And after all these years, we became an open fire, which burned us both (two timeless flames)

Disconnected

By Beba Kuka

In the past few days, I have often found myself thinking about the people I have met over the past few years. I have recalled their stories, their paths through life, their glances, their smiles, their curiosity and bewilderment. The ones who have remained most vivid in my memory are those who, in one way or another, have become disconnected.

During my travels, I met several remarkable women, extraordinary in every sense. Highly educated, with wide-ranging interests; some mothers, some wives, some entirely free, yet all of them intensely curious and full of vitality. Women who, at some point, whether through waning motivation in their careers, the demands of motherhood, the decision to follow and support their husbands, or the dissatisfaction born of limited personal choices, had become disconnected. Not alienated, simply disconnected.

I also met men who had graduated from good universities, held well-paid jobs, and were on promising career paths, yet who, at a certain moment, chose to walk away. They did not abandon work itself, but rather their former lives and everything that had defined them. Many of them, too, became disconnected.

While I was in India, I felt as though everywhere I went, I encountered only disconnected people, as if there were no others. And then I realized that, in each of them, I was recognizing a part of myself I had never been aware of before. That, perhaps unconsciously, I had surrounded myself with people in whom I sought echoes of my own undefined self, something that was undeniably part of me, though I had not known what to call it.

Until I understood that I, too, am disconnected.

Only then did it become clear why I am drawn to such people, why I understand their stories, their need to move, to search, to explore, to question. It is because I know what it feels like to find no understanding for one’s way of life, choices, or decisions. I was fortunate to have the unwavering support of my parents, yet even some of my closest friends did not understand my decision to resign from my job and travel the world alone.

I realized that I understand, and deeply feel, the disconnected person’s desire to leave everything behind, to disappear, to erase what has been, and to begin again. And again. And again. I recognize the imbalance between what one feels, deep within, to be one’s true self and what one must become to survive in this world. I know the inner struggle between the part of me that is Beba, the woman who rides horses freely across the Patagonian pampas, and the Beba who responsibly manages a multi-million-dollar international fund. Both are me, though at times it is difficult to bridge the space between them, to find harmony across time, emotion, desire, and reality.

I came to see that this feeling, of not belonging to one’s homeland, of not fitting into the environment that is supposedly ‘natural’ or that one currently inhabits for work, family, or obligation, is precisely what all disconnected people share. A sense of being out of step with one’s surroundings, with the general rhythm of thought and life.

Some of the people I met had lost their confidence, their spark, the trigger that once set their lives alight. Feeling misunderstood, they had withdrawn, watching their own existence as though it belonged to someone else. Thankfully, most of them continued to explore, to seek new experiences, with greater curiosity and passion than ever before. They adapted to new cultures and traditions, and to the roads that opened before them, or that they forged themselves.

Some of the disconnected, like me, without children, free of fixed obligations, and financially independent, have the privilege and luxury to say: ‘I’ve decided to leave my job, to travel for a year, to learn a new language, to meet new people, to ask questions, to wander and lose myself, to do whatever I please, to discover what still makes me happy.’

And that freedom of choice, I now realize, is an immense luxury. It is hard for me to imagine, and thank God I do not have to, what it must feel like to be disconnected and yet have no choice, no door or even a window through which to escape from what makes you despair, what keeps you from connecting with someone or something, whether kindred or completely different.

And yet, perhaps that very freedom is a double-edged sword. Perhaps the abundance of possibilities, the knowledge that you can leave at any time, start anew whenever you wish, perhaps it is precisely that which prevents you from giving your best, from finding contentment in what you already have. From adapting, from discovering within yourself a small, hidden part you never knew existed, because, until now, you simply had no need for it. Perhaps. But for now, being disconnected feels as a blessing.

Personal Images: Expecting

By Lyla Rose

There was a part of her that liked being on stage, liked performing. It was the same sort of thrill she got from sending a naked photo, knowing it was good, even before the three little dots started bouncing up and down at the bottom of her screen.

Sometimes, she needed someone to take her home at night, the tall guy at the bar, a stranger, it could be anyone. Just to be looked at in the soft glow of her Ikea lamp with the cloth napkin draped over it. To be ogled at, explored, like a sculptor examining his work fresh out of the kiln.

They’d leave, slipping back into the same dark night they came from. Normally, she wouldn’t have cum so she’d scroll on her phone for hours, her energy still trapped there, right underneath her skin. Her dark hair and green eyes illuminated by her phone screen while her fingers tapped, swiping left and right on dating apps.

This felt constant. This state of searching.

She couldn’t wrap her head around the couples she saw on Instagram for Valentine’s Day.

When had these people met? Had they all gone to some giant speed dating event that she had missed? She got the uneasy feeling that everyone had already met their lovers, their best friends, that she was standing outside of some sort of snow globe, peering in, her face pushed up to the glass.

She peaked in the top right corner of her screen. 1:47am. And she had work in the morning.

She oscillated between two feelings: 1. I don’t need anyone, I should be focusing on myself and 2. if I had SOMEONE then I would really BE my full self.

She hated when people said love comes when you least expect it, when you’re not looking for it.

But what if you’re always searching?

She tries to think about moments she hasn’t been searching and yet, even when she’s been in relationships, the searching has remained.

She’s felt happy, yes, pleased even by their personalities. And yet, she still searched them over, like an intake at a sterile doctor’s office. Their relationships with their parents. Their high school experience. What did they think about sexuality?

Sometimes small opinions could make her lose interest entirely, suddenly. Her attention like a lighthouse, suddenly shifting, illuminating some other object as her previous lover lies in the dark.

She wanted so desperately to be loved by someone and yet she hadn’t thought about what sort of love she should be looking for. She cursed her parents. She had never seen it work. Her only framework provided by rom-coms and other people’s relationships she knew she didn’t want.

How does one stop searching? She thought it might be a good idea to get absorbed in her hobbies. What were her hobbies? She googled things, made lists, she took buses and bikes and trains to events speckled throughout the city. Zig-zagging her way, making impossible shapes on maps. She started building c-o-m-m-u-n-i-t-y. Something she had always thought didn’t include her, didn’t apply. Another snow globe.

To her surprise, her dramatic ways were welcomed by the comedy club. They were tall and small and had bad haircuts. They wore torn clothes and she didn’t have to try hard to make them laugh. She laughed too.

Comedy class would end and her colleagues would trickle to the nearby bar. They’d drink too much and make rude gestures to the bar tenders they thought were cute.

There was a man who looked more like a boy in her comedy class. He talked too much and he would remind people to tell him to shut up. The first class people were too shy to do it but by now, her classmates would periodically yell: SHUT UP STEPHEN.

He didn’t care, he said. People have been saying that to him his whole life.

One night after a spectacularly bad show, the group flocked to the bar with dark wooden floors stained with beer and Shut Up Stephen bought her a beer. He asked if she would pose for him.

I’m an artist, he said. A sculptor.